Inside the tense moment an admiral decided to attack two shipwrecked passengers of a ‘drug boat’ and spark cries of war crimes

Two shirtless people were clinging onto the remains of a vessel in the Caribbean Sea, hoping to flip the wreckage after a U.S. military strike capsized their boat when a second missile struck, officially killing all 11 people on board the alleged drug-carrying vessel.

Ahead of what’s now known as the “double-tap strike” on September 2 — a controversial attack that has sparked allegations of “war crimes” —Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth had ordered U.S. forces “to kill the passengers, sink the boat and destroy the drugs,” three people familiar with the operation told the Washington Post.

A new report now gives insight into the tense moments on September 2 when those decisions were made that day and the decision to kill two shipwrecked members of the alleged drug boat after the initial strike. Those decisions have led some to accuse the U.S. of war crimes and put Hegseth under the microscope.

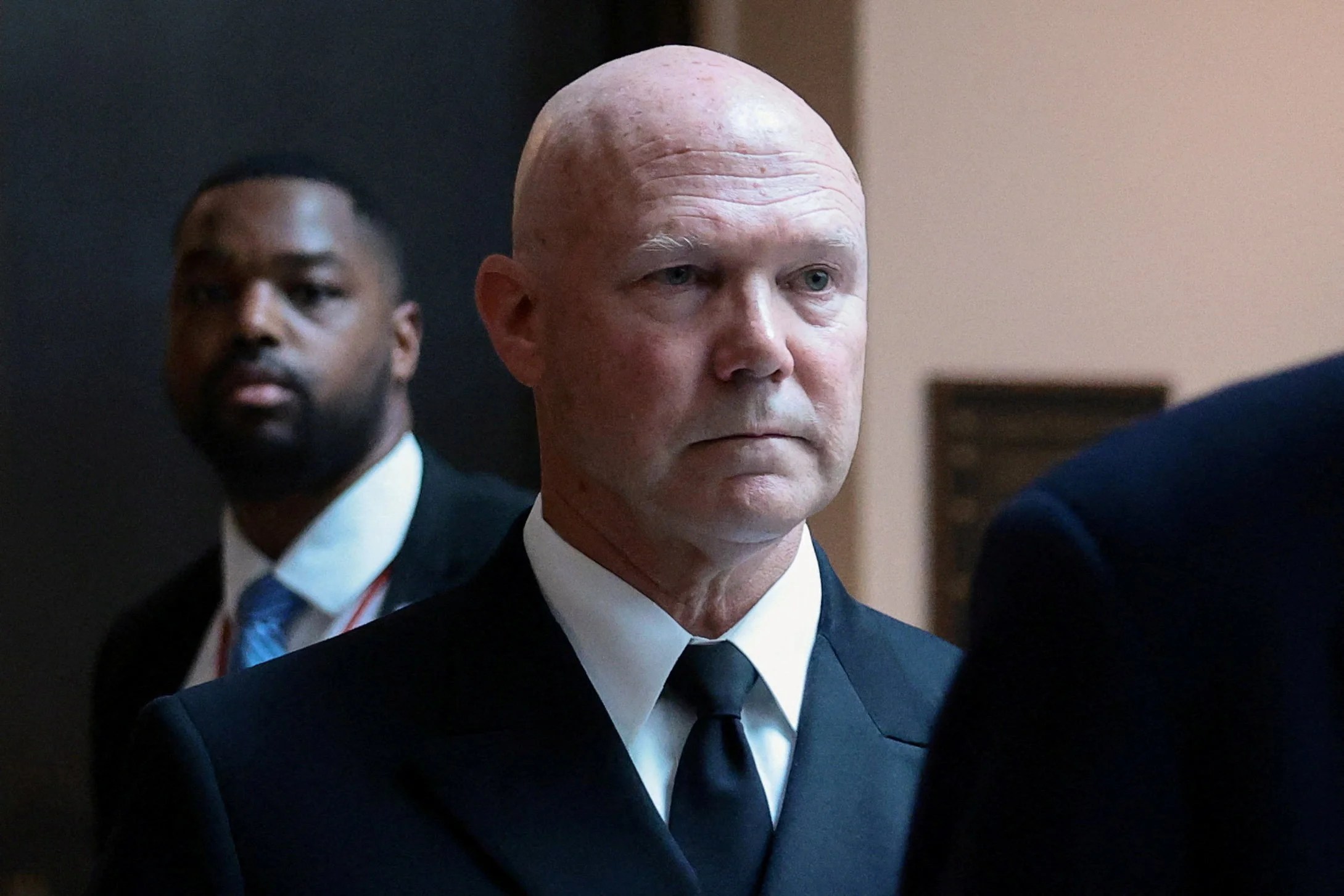

That day, a laser-guided GBU-69 capsized the front end of the boat, sank the boat’s motor, and killed nine on board, the Post reported. But a live surveillance feed — provided by a U.S. aircraft flying overhead — suggested to Navy Adm. Frank “Mitch” Bradley that the mission had not been accomplished. The feed showed two survivors and a damaged boat that could have drifted, Bradley told lawmakers in a closed-door meeting on December 4.

The men were waving their arms overhead, but it wasn’t clear if they were surrendering or had spotted the U.S. aircraft and were seeking help, he said. They were hanging onto wreckage the size of a dining room table, sources told the Post.

Bradley disclosed that it wasn’t clear whether the two shirtless men had communications devices on them or within reach. U.S. intelligence suggested that this boat was planning to “rendezvous” with a larger vessel — bound for Suriname — to transfer drugs, he told members of Congress.

Although the feed didn’t show the larger vessel in the surrounding area and the larger boat wasn’t heading directly for the U.S., the possibility that the drugs could have ultimately wound up in the U.S. still remained, Bradley argued, CNN first reported. All 11 people on board were on a list of “narco-terrorists” whom military and intelligence officials determined could be targeted with lethal measures.

With questions swirling, Bradley asked for advice from the military lawyer. U.S. intelligence showed everyone on board the boat was, what Trump administration officials call, a “narco-terrorist.” The U.S. was engaged in an “armed conflict” with drug cartels. But the question for the lawyer was whether the men were considered “shipwrecked?”

According to international law, “shipwrecked” is defined as those “in a perilous situation at sea” and who “refrain from any act of hostility.” Those shipwrecked “shall be respected and protected” and given swift medical attention. Bradley didn’t reveal where the military lawyer fell on the matter.

But what happened next has made endless headlines: Bradley ordered another strike — using a smaller AGM-176 Griffin missile, the Post reported — that killed both survivors. The U.S. then fired two additional Griffin missiles, sinking the vessel. The admiral argued to lawmakers that he was targeting the boat filled with drugs, not the people.

The attack was one of dozens the U.S. launched against alleged drug-running boats in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean since September, killing at least 80 people.

Hegseth has tried to distance himself from the September 2 attack. The defense secretary said he “didn’t stick around” for the follow-up strikes, and only learned about them a couple hours later. Some lawmakers have asked to see Hegseth’s schedule for that day.

Hegseth has also stood by the admiral, saying he “fully support[ed]” Bradley’s decision and “would have made the same call myself.”

“We are not going to second-guess a commander who did the right thing and was operating well within his legal authority,” Sean Parnell, a spokesman for Hegseth, told the Post.

President Donald Trump has supported Hegseth, saying he has “great confidence” in the defense secretary and believed he didn’t order the strike on the survivors. However, the president conceded last month that he wouldn’t have wanted the second strike.

Trump said last week that the footage of the September 2 attack would “certainly” be released and that it would be “no problem.” This week, he walked back that claim, first denying that he ever said that and then defaulting to Hegseth to make the footage public. “Whatever Pete Hegseth wants to do is OK with me,” Trump said Monday.

Days after Bradley testified, Hegseth didn’t commit to releasing the footage of the controversial strike, but said it was under review.

Congress has launched several probes into the September 2 strike. Bradley met with lawmakers in the Senate and House Armed Services and Intelligence Committees.

Alabama Rep. Mike Dodgers, the Republican chair of the House Armed Services Committee, said this week that he doesn’t see a reason to continue investigating the strike, telling reporters he’s gotten “all the answers I needed.”

Republican Rep. Rick Crawford, chair of the House Intelligence Committee, similarly said he felt “confident and have no further questions of Hegseth.”

However, Democratic Rep. Jim Himes, the ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, told reporters the footage of the lethal strikes was “one of the most troubling things I’ve seen in my time in public service.” He characterized the survivors as being “in clear distress.”

GOP Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee Tom Cotton voiced understanding behind Bradley’s logic, noting that the survivors still posed a threat.

“I saw two survivors trying to flip a boat ― loaded with drugs, bound for the United States ― back over, so they could stay in the fight,” Cotton told reporters after the hearing. “And potentially, given all the context we heard, of other narcoterrorist boats in the area coming to their aid to recover their cargo and recover those narcoterrorists.”

In the Senate Armed Services Committee, the chair and ranking member have requested the executive orders authorizing the operations as well as the complete footage of the attack, Rhode Island Senator Jack Reed, the panel’s top Democrat, told PBS last week.

Meanwhile, Mark Warner, the top Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee, has said he’s requested written documentation of the opinion from the military lawyer who had advised Bradley.

Several legal experts have weighed in on the strike.

According to laws of war, military officials are required to consider the “collateral damage” of a strike only if the move could pose a “threat to civilians,” Geoffrey Corn, a retired Army lawyer, told the Post.

The Department of Defense didn’t need to make that consideration to survivors, Corn argued, because the Trump administration has branded those on board the ship as narcoterrorists — “unlawful combatants” in an “armed conflict” — and the White House has insisted the strikes were conducted “in self-defense.”

The retired Army lawyer argued that even if the survivors were “combatants,” they were shipwrecked, meaning they could have been rescued before another strike was launched.

“That to me is the most troubling aspect of the attack,” he told the Post.

Todd Huntley, a former director of the Navy’s international law office, told the paper that the legal definition for being shipwrecked just means “they just have to be in distress in water.”

He also said that whether they had communications devices on them shouldn’t have been taken into consideration. “You can’t kill somebody in the water merely because they have a radio,” Huntley told the outlet.

He also disputed the idea that a potential rendezvous with another boat suggested the survivors posed a threat: “That is such a far-out theory.”