A recently unveiled memo from the Department of Justice indicates Donald Trump’s administration plans to “maximally pursue” denaturalization of American citizens, marking a radical expansion of the president’s anti-immigration agenda.

According to the June 11 memo, the Justice Department’s civil division will “prioritize and maximally pursue denaturalization proceedings in all cases permitted by law and supported by the evidence.”

The agency intends to take action against citizens who it believes “pose a potential danger to national security,” or who officials claim have acquired their citizenship through “material misrepresentations.” The division also notes that it could pursue denaturalization in “any other cases” that officials believe are “sufficiently important to pursue.”

“These categories do not limit the Civil Division from pursuing any particular case, nor are they listed in a particular order of importance,” according to the memo.

Immigration attorneys and advocacy groups warn that such sweeping guidelines — fueled by a politically motivated agenda — could end up targeting a broad spectrum of U.S. citizens.

Is that legal?

Trump wouldn’t be the first president to strip citizenship from naturalized citizens, but it’s an exceedingly rare measure; the government pursued an average of 11 denaturalization cases between 1990 and 2017, when the first Trump administration began ramping up efforts to strip American citizenship, according to the Immigrant Legal Resource Center.

Roughly 25 million people in the United States are naturalized citizens, or immigrants who completed the lengthy legal process to become a citizen.

More than 22,000 Americans were denaturalized following the the Naturalization Act of 1906 through 1967, but those efforts largely dissipated following that year’s landmark Supreme Court ruling that held that denaturalization is unconstitutional in most circumstances, unless an immigrant had “illegally procured” citizenship through fraud or other means.

“Citizenship is no light trifle to be jeopardized any moment Congress decides to do so under the names of one of its general or implied grants of power,” Justice Hugo Black wrote in the court’s majority opinion.”

But by 2020, the first Trump administration had filed 94 denaturalization cases. Joe Biden’s administration had pursued 64 such cases.

The first Trump administration also opened a “Denaturalization Section” within the Justice Department’s Office of Immigration Litigation to specifically investigate and prosecute a “growing number of referrals anticipated from law enforcement agencies.”

How does denaturalization work?

Under the Justice Department, denaturalization cases would play out in civil courts, where there is a lower burden of proof than criminal cases, no statute of limitations, and no right to an attorney.

While criminal defendants receive court-appointed attorneys, a right to a jury trial and a verdict of proof “beyond a reasonable doubt,” there are no such guarantees through a civil process.

The burden of proof is “clear and convincing evidence” rather than “beyond a reasonable doubt,” and a judge — without a jury present — makes that decision.

The Justice Department’s new criteria in its June 11 memo — which calls on prosecutors to open “any” case they determine are “sufficiently important” — opens the door for “opaque and arbitrary” enforcement, according to George Mason University immigration economics professor Michael Clemens.

That language gives the government “wide discretion” to decide who to target, according to Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law professor emeritus Steve Lubet.

“Many of the categories are so vague as to be meaningless,” he told NPR. “It isn’t even clear that they relate to fraudulent procurement, as opposed to post-naturalization conduct.”

Lubet also feared the far-reaching “ripple effects” of stripping citizenship for a wider range of citizens, which could threaten families with mixed legal status, particularly natural-born citizens whose parents’ lost their citizenship.

“People who thought they were safely American and had done nothing wrong can suddenly be at risk of losing citizenship,” he added.

Who is targeted?

The White House has used citizenship as a cudgel in his government-wide deportation project, with administration officials and Republican members of Congress threatening to strip citizenship from their political enemies.

Last week, Republican Rep. Andy Ogles sent a letter to Attorney General Pam Bondi demanding a federal investigation to determine whether New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani — a naturalized U.S. citizen who was born in Uganda — should be stripped of his citizenship.

On June 10, White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt indicated that the allegations against him “should be investigated.”

Some Republican officials are also cheering on the revival of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s notorious Un-American Activities Committee and calling on the president to invoke the Communist Control Act, the decades-old law that ostensibly targeted Communist Party members and prohibited communists from certain public roles.

The act has since faced a wave of legal challenges as a McCarthyist relic of the red scare era.

“New York City is on the verge of electing a socialist for mayor,” Republican Sen. Mike Collins wrote last week. “Might be time to bring back the committee.”

The Justice Department’s latest memo also echoes Stephen Miller’s 2023 pledge that the first administration’s “denaturalization project” would be “turbocharged” under a second Trump administration.

Miller, Trump’s White House deputy chief of staff and a key architect of the president’s anti-immigration agenda, has led efforts across the federal government to aggressively remove immigrants from the country.

Trump has also floated sending U.S.-born citizens to foreign prisons.

“What, you think there’s a special category of person?” he said in remarks from the White House next to Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele in April, following El Salvador’s agreement to detain deportees inside the country’s notorious CECOT prison.

“They’re as bad as anybody that comes in,” Trump said. We have bad ones too.”

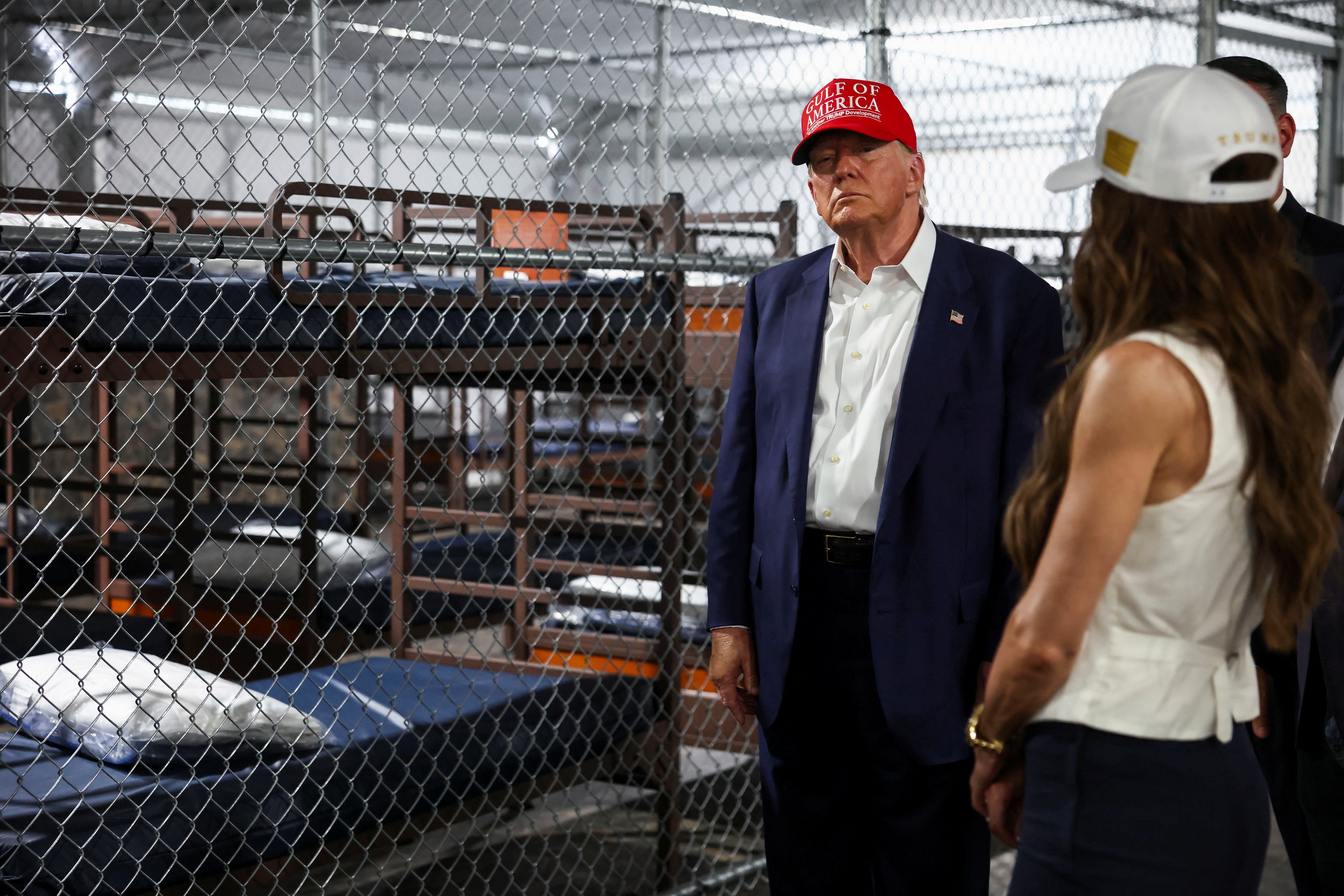

Trump revived the idea of deporting citizens while speaking in Florida on Tuesday during a visit to an expansive new immigration detention center in the Everglades.

“We also have a lot of bad people who have been here a long time,” Trump said.

“Many of them were born in our country,” he added. “I think we ought to get them the hell out of here, too, if you want to know the truth. So maybe that’ll be the next job that we’ll work on together.”

The Trump administration also is pursuing an attempt to unilaterally redefine who is eligible for citizenship.

Shortly after taking office, Trump signed an executive order that seeks to amend the 14th Amendment of the Constitution to exclude citizenship from newborn children born to certain immigrant parents.

Two dozen states, immigrant advocacy groups and pregnant immigrants sued to block the order from taking effect. Several rulings from federal judges and appeals courts issued nationwide injunctions blocking the order, but a ruling from the Supreme Court has limited the scope of those injunctions, teeing up more legal challenges against Trump’s executive order.

The Justice Department intends to return to the Supreme Court with a renewed challenge against birthright citizenship later this year.

Trump’s State Department has moved to strip legal status for thousands of international students, including students with permanent lawful status, over campus demonstrations against Israel’s war in Gaza.

The Trump administration has also stripped legal status for more than 1 million people who were granted humanitarian protections to live and work in the United States — radically expanding the pool of “undocumented” people now vulnerable for arrest and removal.

The administration “de-legalized” roughly 1.4 million immigrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela by stripping their “temporary protected status” designation, intended to legally allow immigrants into the United States who are fleeing disaster, violence and crisis abroad.

Meanwhile, thousands of people with pending immigration cases have been ordered to immigration court hearings and ICE check-in appointments each week only to have their cases dismissed, with federal agents waiting to arrest them.