Wayne Gramlich was there at the very beginning of the Internet. While still in high school in the mid-1970s, the now 69-year-old managed to access the nascent technology — then called the ARPANET — and he decided on MIT for college because it was one of only a handful of universities in the United States at the time that was online.

True to form, the lifelong software engineer and computer enthusiast, who recently retired from Google Brain’s robotics department, still prefers to use a landline, once helped track down a friend’s brother who needed deprogramming from a cult — and in his spare time helped create the Snoo. (He’s signed enough NDA’s that he can’t describe the experience in any detail, but he calls the famous baby crib “probably the most successful robot on the market today”.)

In other words, Wayne Gramlich has led a very interesting life.

But perhaps the most interesting part of all is how he partnered with the poker-playing grandson of the noted economist and statistician Milton Friedman and — along with half a million dollars of Peter Thiel’s funding — attempted to build a libertarian nation-state … on the sea.

“Seasteading” — as Gramlich called it in an early paper, a term that drew a connection with early American homesteads and caught on among Silicon Valley types — was seen as a solution to a lot of things. Libertarians believed governments were broken, cities bloated and land-based civilization a lost cause. The solution to problems like government oversight, as they saw it, was to abandon the nation-state entirely — and start again on floating platforms in international waters.

Did Gramlich himself believe that? No, he says, and he was fairly unimpressed with the pie-in-the-sky ideas of some of the most ardent libertarians around at the time. “I read Atlas Shrugged. I said: Boring, and not very realistic.”

But he did find the engineering problem of building a seastead — basically, a community that floats on the water — extremely interesting. He’d seen people discussing it in early online forums. They always used imagery of flat seas without waves, and their calculations failed to take into account bad weather or dynamic movement. Gramlich thought he could do better.

He started tinkering around with a more realistic version of an overwater city, one that could withstand high winds and disturbance in the water. He thought about a platform made out of plastic bottles lashed together and floating near a shoreline, or an open-seas version that took its inspiration from oil rigs.

Two or three people sent him emails, just to chat, when he published his ideas on his website. Then he got an email that was a little different from the others. It came from Patri Friedman, grandson of the late economist Milton, and he wasn’t just casually interested in seasteading. He was really interested.

“We bounced ideas off each other,” says Gramlich, and then eventually they realized they were both based in Sunnyvale, California. They met up for lunch. They talked some more. Patri was interested in building a libertarian utopia; Wayne wanted to see if building a new nation-state on the water was truly viable from an engineering perspective.

It was a workable partnership, but not always easy.

Seasteading is “not a political problem,” says Gramlich, “and I kept pointing this out to Patri. I said, ‘You know, you can practice any kind of government you want, but you have to have the technology first.’”

There was another group of people who called themselves The Atlantis Project who were also online at the time, and the way they were going about things seemed like a warning sign to Gramlich. “The first thing The Atlantis Project did is they wrote a constitution,” he recalled. “And I’m like, ‘You don’t even have the technology and you have a constitution? That seems kind of silly.’”

Gramlich was now embroiled in the world of tech-forward libertarians, people who would eventually come to refer to themselves as the New Right — with Peter Thiel as their leader and JD Vance one of its main acolytes.

Seasteading would have its dramatic fall and then its renaissance. The small, isolated islands of French Polynesia would get swept up in their ambitions and then dramatically abandoned. Ocean exploration would become an obsession among wealthy interested parties as diverse as James Cameron and Elon Musk. The Silicon Valley-style “move fast and break things” mentality in this space would ultimately lead to the tragedy of the OceanGate submersible implosion.

But none of this had happened yet. It was the early 2000s, and Gramlich and Friedman had lofty goals. Gramlich was sure he could work out the engineering kinks, even if it meant a lot of high-level logistics.

It’s all very good imagining a floating city hundreds of miles off a country’s coast, he says, and you might be able to construct one of those houses for about a million dollars. A lot of people spend a million dollars on a home, which makes a seastead seem within easy reach — “but you have to understand that there’s no infrastructure.”

“You have to import your water. You need a backup generator, you need to have a place to store your diesel for the backup generator. And how are you going to feed yourself? Well, there’s no fish out in the middle of the ocean. It’s a desert, fish-wise. So now you’ve got to import your food. You might say, oh, well, you can do desalination for water — but that takes energy. You don’t have energy. So you’re going to import your water, your food, everything. And for a long time, there was nothing to do out in the middle of the ocean, because we didn’t have Starlink, so you didn’t have the internet or anything either.”

None of this seemed like a huge deal to Patri. He was busy putting together a 331-page ebook (titled “Seasteading: A Practical Guide to Homesteading the High Seas”) which featured lofty pronouncements like: “Imagine the tremendous possibility of being able to create new acreage on the vast and empty oceans. The environment may be less friendly, but the increased freedom will appeal to a motivated minority who are fed up with terrestrial politics. These aquatic pioneers will settle civilization’s next frontier through the unusual merger of green technology and free enterprise. Once there, they will experiment with new social, political, and economic systems, adding much-needed variety and innovation to the stagnant business of government.”

“That is quite normal for this group of people,” says Gramlich.

He has a lot of respect for libertarians, even if he doesn’t share their politics, and he underlines that he eventually parted ways with Patri amicably, even if the parting was painful for a while. However, he says, one thing about Silicon Valley techno-libertarians pursuing these kinds of projects is undeniable: “They get excited.”

Tsunamis, pirates and crypto-anarchy

It was Patri Friedman’s excitement that led to the funding. Six years after he and Gramlich started working together on the idea of a seastead, Friedman went for a job interview where he mentioned the project and word made its way to new multimillionaire Peter Thiel. Thiel was the founder of PayPal and a then-rare conservative in the tech space, who in 2002 had made $55 million from the sale of PayPal to eBay.

Thiel wanted to use his newfound fortune to further some of his most ambitious political ideas, and seasteading piqued his interest. He reached out to Patri Friedman and offered him and Gramlich $500,000 in seed funding to make seasteading a reality. He also helped arrange some working space for Friedman and Gramlich at the offices of controversial data-mining company Palantir (“I thought it was kind of weird because Palantir was doing all that security clearance stuff,” says Wayne. “I can’t believe that they let us get a — well, we didn’t have an office. We just had a nook.”)

In early 2008, The Seasteading Institute was born. Friedman carried on writing the ebook. Gramlich plugged away at the engineering problems. They had meetings about structure designs — undersea resorts or floating homes? Oil rig-style or houseboat-style? — and possible hazards (tsunamis, high winds, sewer ice, geopolitics and pirates.) They talked about health tourism and daily rations of beer and “crypto-anarchy”. They theorized on how to respond to the criticism that, in the words of their ebook, “it’s just a bunch of rich guys wanting even more freedom.”

Thiel had made it clear, says Gramlich, that part of The Seasteading Institute’s remit was simply to popularize the idea of seasteading itself. Friedman diligently worked on that, while Gramlich researched sea laws and eventually gained an encyclopedic knowledge of maritime legalities (for instance, he tells me, there’s a long-standing law in the US that complicates getting supplies to Puerto Rico whenever it has a hurricane. The law says that a boat made in a different country to the United States cannot sail from one American port to another. But because almost no American cargo ships are actually made inside the US, that means the country can’t easily send its own supplies from an American port to a Puerto Rican one, since it’s an American territory.)

Gramlich wanted to conserve the cash, to be careful with the money. But by now, another one of Thiel’s acolytes, Joe Lonsdale, was on the board, and Joe and Patri were emboldened by the cash and excited by the possibilities. They voted to go ahead and build a large seastead right away, overruling Gramlich, who wanted to start small. In the background, a global financial crisis was looming.

The French Polynesian experiment

Marc Collins Chen says it’s absolutely his fault that The Seasteading Institute got involved with French Polynesia. He may be the CTO of Oceanix now, working on a floating city off the shores of Busan in South Korea which he says will start construction in 2026, but he was once a seasteading enthusiast in the French Polynesian government.

Not long after they received their half a million dollars in funding from Thiel, The Seasteading Institute approached French Polynesia with an idea: Since they’d realized that building all their infrastructure from scratch would be logistically untenable, could they build a few miles off the shores of the islands instead? They could take advantage of the fiber-optic undersea cables that deliver high-speed internet to French Polynesia, as well as hooking up to some of their other existing infrastructure, all the while remaining in one of the most isolated parts of the world. It sounded innovative and a little crazy, but perhaps worth an experiment. Few could have imagined how badly it would go down with the islands’ residents.

Collins Chen doesn’t mince his words: “I am fully responsible for both bringing them in — and for it probably failing as well.”

The Seasteading Institute was “looking for a host nation” when they approached him, he says, and at first it seemed like a win-win situation. French Polynesia is sinking, mainly due to rising seawater levels from climate change. It faces disappearing completely by the end of the century if nothing can be done. Working out how to construct workable floating seasteads is clearly a potential solution for a nation desperate to survive.

French Polynesia’s government drew up a seven-year agreement — a “memorandum of understanding,” says Collins Chen — with The Seasteading Institute, and both hoped to get work underway promptly. But then negotiations began to get heated.

“What did not work [for us] was this idea of a carve-out, whether it’s for taxes or whether it’s for labor laws, and it became untenable,” he says. “I mean, there are Nobel Prize economists who have written whole theses on charter cities. But when you’re from the global south, those things — they have a neo-colonial sort of flavor to them.”

Collins Chen says he soon realized that “what they seemed to be imagining was a kind of floating island for tech billionaires who wanted to live a low-rules and -regulations kind of life, while also using the resources — like tech resources and things — from French Polynesia.” The project did start, however, and it was a bold attempt at logistical engineering that had never been attempted before. The engineering side went well. The ideological side did not.

“Politicians sometimes have to look at gradients, right? And say: OK, so is this technology potentially usable in the Pacific? Yes. Is the political, ideological event acceptable to our people? And it turned out that it wasn’t,” says Collins Chen. “And I was the first to start raising that with our US partners and saying: Look, let’s work on the technology. Before you start talking about governance and what you need in taxes and all this, you actually need a thing, right? You need a floating piece of infrastructure.”

Unfortunately, quietly building in the ocean wasn’t what Patri Friedman had imagined. He had the ebook, the funding contingent on popularizing the idea, the Silicon Valley libertarian network. Now, he had a government interested in a partnership. Why wouldn’t he spread the word?

What comes after techno-colonialism

In August 2007, a video game was launched that would change the industry. BioShock featured an underwater city built by a business magnate and cut off from the outside world, a metropolis constructed by social elites on libertarian values. Sick of government control, Earth’s billionaires had gone bravely into the ocean, convinced that they were going to forge an Ayn Rand-inspired utopia. They called it Rapture.

Visually arresting and narratively complex, BioShock received rave reviews and spawned two extremely popular sequels. It is generally considered to be one of the greatest video games ever made. The Seasteading Institute clearly has some direct parallels with BioShock, though its founders have never publicly acknowledged it. Nevertheless, those parallels with the enormously successful video game seemed to underline how much the real world had become an extended playground for the impossibly rich.

If you’ve played BioShock, you’ll know that the utopian underwater city didn’t actually succeed for the fictional founders. The entire game is based in a distinctly dystopian aftermath, where the underwater city has descended into chaos following extreme social inequity and genetic engineering gone wrong. And yet Peter Thiel wrote his $500,000 check to The Seasteading Institute less than a year after BioShock changed the cultural conversation. Was there something he saw that everybody else didn’t — or is it the other way around?

Environmental scientist and Professor of Sustainability Peter Newman is one of the most outspoken critics of seasteading, having once called it “apartheid of the worst kind”. In an email interview from his home in Perth, Australia, he espouses similar views: “Whether it is privatised urbanism or techno-libertarian escape, the idea is pretty stupid,” he tells me. It is, he adds later, “a rich people’s diversion and has no obvious value”.

Newman believes seasteaders willfully ignored the obvious logistical problems with their idea, including — most urgently — the continually warming ocean, which deposits more energy into the sea and means “unpredictable ocean activity that will be focused on shorelines”.

“I can’t imagine a more dangerous site than this” to build on, he adds, apart from perhaps the riverbed in Texas. And fundamentally, he believes, seasteaders are naive to the point of hypocrisy: “As soon as a seasteader falls seriously ill or there is a damaging weather event, the residents will no doubt rush to all those services provided on the land, especially in any nearby city, and demand their rights to be looked after.”

The years after French Polynesia signed their seven-year agreement with The Seasteading Institute proved to be tougher than expected. As the project was hammered out, designed, redesigned, and talked about incessantly in American libertarian circles, the general populace on the islands began to get uneasy. French Polynesians organized protests against “techno-colonialism” and about the use of the country’s fishing grounds as a food source for a new floating island of billionaires; in 2017, hundreds of anti-seasteading activists marched in the capital of Tahiti.

That was the final nail in the coffin of the agreement, says Collins Chen. The government announced that their seven-year agreement had lapsed with the Institute anyway, and they would not be renewing it.

Collins Chen remains philosophical about the whole endeavor. “It did move the whole industry forward,” he says. “I think that was the biggest seminal moment in our industry.” When co-founding Oceanix, he was determined to learn from The Seasteading Institute’s mistakes. Oceanix is an apolitical entity, and describes itself as “new land for coastal cities looking for sustainable ways to expand onto the ocean, while adapting to sea level rise.” Its Busan prototype is partially funded by the UN’s environmental arm. The focus is much more on ameliorating climate change’s effects and much less on creating a libertarian paradise.

Collins Chen’s focus was on “what do we do as Pacific Islanders to mitigate against this what seems like unstoppable force?” he says.

“Telling your people to move — and particularly in the context of our culture, where we bury our ancestors on our property, on our land — nobody was ready to start moving bodies and saying, Hey, well, let’s give up and move. So then you start looking at technology.”

His time in the French Polynesian government made him realize that trying to convince countries to give up even a “tiny part of their sovereignty” is a disaster, so negotiations with the city of Busan and the government of South Korea have been careful and collaborative.

As Collins Chen sees it, Oceanix is a much more realistic version of seasteading. It’s not positioned 200 miles off the coast of the mainland. And it’s not concerned with isolating people and allowing them to live on little self-sustaining pods that can float off into the beyond if they disagree with their neighbors’ politics. Nine out of 10 major global cities in the developed world are coastal, and we need to “double the built environment over the next 40 years” to deal with the world’s exploding population, he adds. Adding to the coastlines of major cities just makes sense.

“There’s a reason people go to cities,” he says. “There’s a reason everybody’s moving to cities around the world. It’s where the market is, it’s where you can trade. It’s where you can find a mate. It’s all of the reasons you don’t just go in the middle of the ocean and be with a bunch of burners.”

“The most positive way to look at seasteading is that it has a pioneering mentality which is seeking to go where no humans have dared to go,” Peter Newman adds, “like going to the Moon or Mars. Many aspects of human life have been improved by daring pioneers.

“But I also think that this is misplaced in a time when climate damage is killing so many people and so much biodiversity, and threatening so much that is good about our cities and agriculture. I don’t believe there is any point in investing in [the] Moon, Mars or seasteads when we are desperately needing to focus on how to bring down global warming so we can return to a safe operating space like we have had in our cities and agriculture for the past 12,000 years.”

100 days underwater and the deep-sea cure for Alzheimer’s

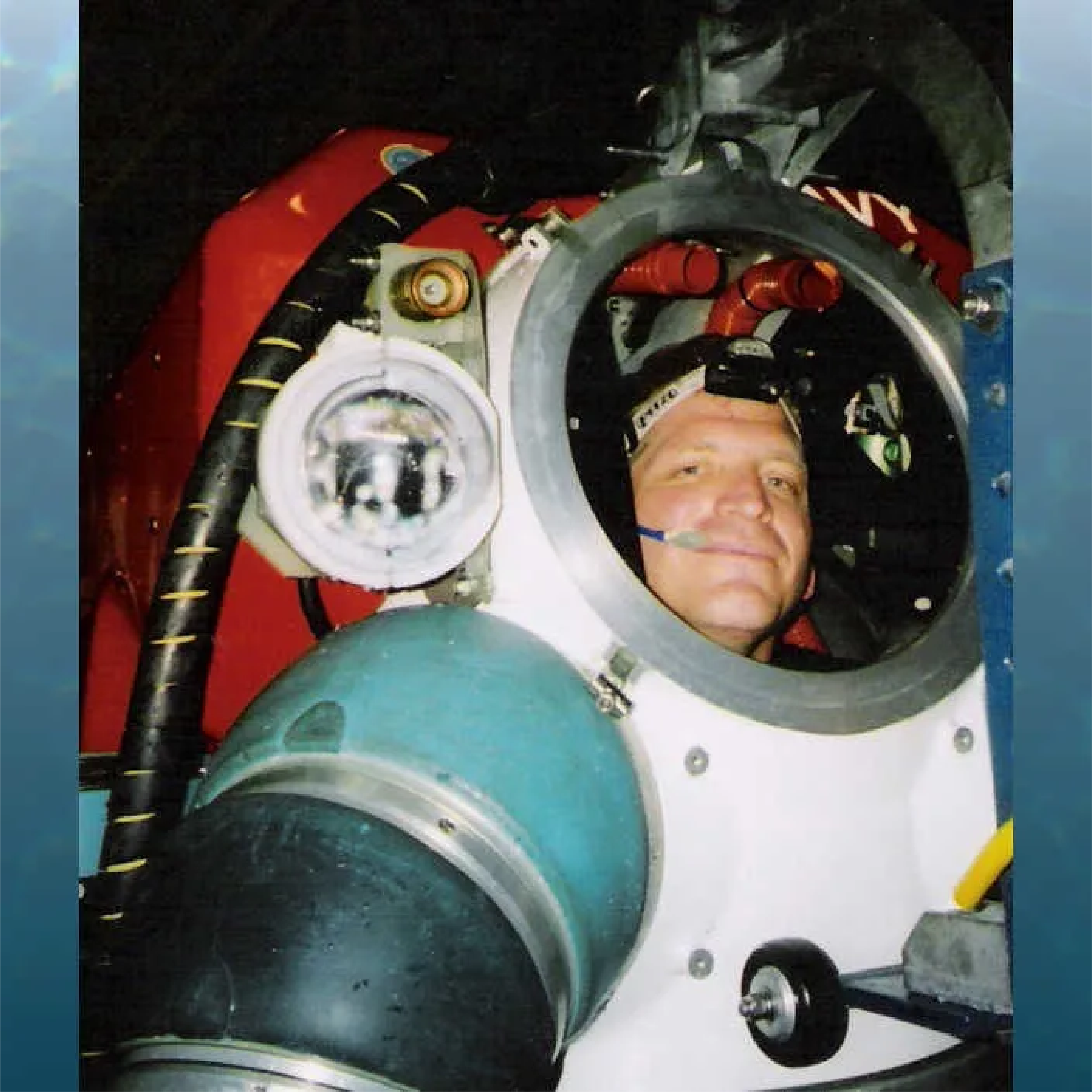

Not long after he retired from the Navy, Joseph Dituri was contacted out of the blue by the movie director James Cameron. Dituri had worked a very specific and specialized job in the Navy: he was a submersible diver, a type of deep-sea diver who spends between 28 and 35 days at a time underwater in very small teams. In pitch-black darkness and freezing temperatures, submersible divers do the work that few others are brave enough to do: submarine rescue, underwater ship repair, marine salvage. Due to the hostile environment and the oppressive water pressures they operate in, every mission means risking their lives. Dituri did it for 28 years.

One might assume that after almost three decades of operating deep underwater, a person might have had their fill. But not Joseph Dituri. He almost immediately threw himself into biomedical research at the University of South Florida, with a focus on deep-sea exploration. That’s where James Cameron came in.

“James Cameron’s people reached out to me,” he says. “He had at that time just been trying to go or was going to the bottom of the Mariana Trench.”

The Titanic director has a personal passion for deep-sea exploration, it turned out. He’d even commissioned his own submersible craft for his hobby. “Well, he went down there and when he came back, he wanted to know what the submersible was worth because he was going to loan it to Woods Hole [Oceanographic Institution],” Dituri adds.

Because Dituri was an expert in submersibles, it was assumed he’d be able to look over Cameron’s craft and give him an honest appraisal. It all moved pretty quickly: an email, a question, and then a plane ticket sent to fly him out to the director’s multimillion-dollar oceanfront ranch in California. Not long afterwards, Dituri says, “I’m standing on the beach at James Cameron’s house, walking his dog, talking to the group about the undersea expedition that he just went on.”

That was surreal enough, but then Dituri and Cameron got to talking about what Cameron had found during his trips under the sea. It turned out that he’d come across a rare type of sea lice at the bottom of the western Pacific Ocean, something that only grows to about a centimeter long at higher depths but, down there in the Mariana Trench, had grown to about a foot and a half long. “So when we found that,” says Dituri, “we pulled a DNA sample on it, and it’s a partial cure for Alzheimer’s.”

The existence of anti-Alzheimer’s molecules in the deep sea — a discovery that is still so early that it needs to be worked out exactly how they could be used to benefit people on land suffering from dementia — stunned Dituri. He remembers running the data on Christmas Eve in 2013, pulling an all-nighter in the lab to get the DNA sample results back to Cameron.

“He wanted the report done by Christmas,” says Dituri. “So I’m writing this report on the 24th, pulling an all-nighter misery, going over the data, combing everything. I finally come to these results from the DNA sample, and I went: Oh my God. We have the dark, we have the light, we have the ying, we have the yang, we have the disease. Wow. We can have the cure. And I put my hands back and I put my feet up on the desk and I said: Oh my God, we have to live in the ocean. And everybody’s like: You’ve lost it. You’re insane.”

Dituri laughs heartily. To this day, he thinks about that revelation as a turning point. It made him realize that the future of humanity lay right back where he’d worked as a submersible diver for so many years: “I mean, there’s a partial cure for a disease that afflicts humanity existing at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, and we didn’t know it was there.”

If you’ve heard of Dituri — a perennial ocean enthusiast and doggedly enthusiastic public speaker who often uses the moniker “Dr. Deep Sea” — it might be because of what happened next. He decided to construct an undersea chamber and live in it for a world record-breaking 100 days. Not only would it be an interesting personal challenge, he reasoned, but it would be an opportunity to quietly observe marine life in a way nobody else had before.

Researchers go underwater all the time in biomedicine (we recently discovered a powerful new antiviral derived from a sea sponge, he tells me) but they don’t often stay long enough to see the really unusual creatures come out. It was reasonable to assume that, once the fish and other marine life got used to his presence among them, they’d start to behave in new and interesting ways.

He’d already stayed underwater in a small team for up to a month. “And when you do that, you’ve got to pick your team very carefully, right?” he says. “You’ve got to make sure that Johnny and Billy don’t go together because they used to date the same girl back in high school or something. All this crazy stuff that comes up. You have to choose your friends wisely at this point, because you’re not going to change them out for a new version.” He’d also undergone the Navy’s brutal and notorious ‘Pool Week’ training, where other divers attempt to drown you in different ways in a controlled environment so you know exactly how to react in any emergency situation.

Nevertheless, being completely isolated for 100 days in a stationary structure 30 feet below Florida’s Key Largo lagoon necessitated mental preparation. And by this point, Dituri was 55 years old. This was a far cry from a normal retirement hobby. “Basically when you look at yourself and there’s nowhere else to go, and there’s nobody else to look at… you’re looking inwardly,” he says. “And holy mackerel, you learn a lot about yourself. And it is a deep, dark, scary experiment.”

Dituri completed his mission and emerged triumphantly back into sunlight in June 2023. He wasn’t that bothered about the world record, he says: he had discovered two new species while down there, partly because the marine life had grown accustomed to him and partly because his own eyes had become uniquely focused on minor changes in the environment. He adds that his experience is also instructive for people planning Mars missions in the future.

The sea has long been a training ground for space exploration. Robotics developed for exploring ocean floors informed planetary rover systems; efficient life support systems that can be used under the sea can be repurposed for missions to Mars; underwater habitats mimic the experience of astronauts on long voyages.

But Dituri thinks we should focus on building in the ocean first. The only problem is that it’s actually a lot harder to build structures at the bottom of the Mariana Trench than it is on Mars. For one thing, the atmospheric pressure is more of a challenge that deep in our own sea than it is in outer space. And for another, a space station is a veritable luxury resort compared to the tiny structures submersible divers have to live inside in between jobs while stationed at the bottom of the ocean.

If there’s going to be human cities under the sea, says Dituri, “sign me up.” He believes that it’s almost inevitable we’ll have to migrate underwater in the future. But he’s wary of Silicon Valley seasteaders whose excitement and ideology comes first and scientific knowhow comes second, especially at a time when the mainstream discourse seems to be moving against established science. He’s also seen firsthand the damage that big business can do to delicate marine environments.

“Science wins over bull*** every time,” he says. “And there’s enough disinformation or misinformation out there. We need the scientific background. Yes, we need to figure out what’s actually going on, but we need to temper that with what works. So we basically need to start doing science in our oceans and protecting, preserving and rejuvenating our marine environment. And then hopefully the planet’s going to come back from the stupidity that we’re enforcing upon it.”

The rise, fall, and rise again of seasteading

The reason Wayne Gramlich left The Seasteading Institute, in the end, wasn’t because of the collapsed deal with French Polynesia or the fact that they’d designed a very large, very expensive seastead that immediately became financially unworkable after the 2008 financial crash. It was because of a new project Friedman decided to spearhead called Ephemerisle.

Ephemerisle — which remains an annual event to this day — is a floating city off the shores of Sacramento that takes shape according to who arrives. It’s a sort of a Burning Man in the ocean, but with no tickets, no stewards and no rules. If you can find a way to turn up, on some kind of a seaworthy vessel that is able to attach to the other vessels in situ, then you can stay. Every July, the gathering encourages “thinkers, doers, artists, dreamers, muckrakers, and builders interested in life on the water” to join in. Once nominally overseen by The Seasteading Institute, it has since become an autonomous set of individual islands. Although the institute officially continues, no one responds to its official email address, and Ephemerisle is all that exists in the physical world of its work.

When they first launched it, Patri Friedman loved the idea of Ephemerisle and thought it neatly fit into the remit of popularizing seasteading as a concept; Wayne Gramlich was sure someone would get killed. It was too risky, too unserious, and too disconnected from the reasons why he was interested in seasteading in the first place. He left the board not long after it launched in late 2009. He sensed Patri’s disappointment, but it just wasn’t aligned with his interests any more.

Worryingly, it seems like some members of the New Right are interested in sea and space exploration simply because they think that the problems they’ve helped create on Earth are not fixable. Either that, or they simply don’t believe they should be subject to any government’s laws now they’ve accrued enough cash to live outside a community.

Although he also stepped away from The Seasteading Institute a few years after its French Polynesian experiment failed, Patri Friedman is still clearly focused on building something ideologically similar. An image he shared from his Instagram account in 2024 shows the words “Voting,” “Violence,” and “Apathy” crossed out, with the final phrase left uncrossed: “Exit and Build”. Accompanying the image, he wrote: “Now that is a sick-ass T-shirt. I bought one on sight from [right-leaning libertarian website] The Conscious Resistance Network.”

Friedman has some other niche interests, including cryogenic freezing after death and the idea of “transhumanism”, i.e. becoming a human-robot hybrid in pursuit of eternal life. He’s also now a partner at the VC firm Pronomos Capital, which invests in charter cities: cities owned by developed countries or wealthy benefactors that sit within developing countries’ land. These are the cities that Marc Collins Chen said seem dangerously close to neo-colonialism. The Independent reached out to Patri Friedman a number of times for comment but he never replied.

From redesigning countries from the inside out to redesigning human beings as 200-year-living quasi-robots, the New Right has an obsession with changing reality. Scientists have long sought to do the same — but Silicon Valley conservatives seek to reshape the world mainly with vast amounts of money and vibes. Their ambitious technological aims sit uncomfortably with their frequent rejection of established science.

Their pervasive belief that if you throw enough money at a nice-sounding idea, it will simply come true has led to such huge missteps as Theranos, the multimillion-dollar-backed startup and former Silicon Valley darling that tried to make instant pinprick blood tests a thing — and then resorted to lying and cover-ups when the founders discovered they couldn’t. Its founder, Elizabeth Holmes, is currently serving 11 years in a Texas prison for fraud.

Nothing underlines the problems inherent in this strategy more tragically than the OceanGate disaster. In June 2023, a carbon-fiber submersible built by a maverick company promising to democratize deep-sea exploration imploded during a tourist expedition to the Titanic wreck. Five people died instantly.

Though not a seasteading project per se, the disaster exposed the same ethos: private ambition outpacing oversight, engineering optimism blinding risk, rich men testing limits with little accountability. When the dust settled — or rather, when the debris was finally recovered — it was hard not to draw a line between OceanGate’s founder Stockton Rush and some of the zanier branches of the original seasteading cohort. Both largely rejected bureaucratic safety checks, or thought they could negotiate their way around them. Both held deep contempt for regulatory bodies. Both wanted to skip the slow, hard work of collective systems in favor of individual will.

Rush had said it plainly: “At some point, safety just is pure waste.” The final US Coast Guard report into the OceanGate disaster strongly criticized Rush — who they said had been warned multiple times about the safety of his submersibles and had dismissed everyone, in favor of a Fyre Festival-style “just smile and it’ll work” mentality — and called the implosion “preventable”.

Peter Newman, the environmental scientist, has visited numerous eco-villages around the world — including the Arizonan eco-village Arcosanti and the off-grid, autonomous Earthships structures built in deserted areas around the US — and “they are all attempts at building community and using recycled materials and renewable energy,” he says. Admirable enough, but not mainstream, and mostly focused on surviving rather than thriving. “However,” adds Newman, “now we are rebuilding our cities with different materials and different renewable energy sources on a different scale that enables us to keep the benefits of large-scale cities with their health, education, employment and community opportunities. This is the big agenda.” The rest is just an expensive distraction.

As interest in seasteading renews, Newman’s eco-villages and Collins Chen’s Oceanix experiment on the shorelines of Busan seem a lot more encouraging as blueprints. But in the background, the fever dream of techno-libertarianism where wealth replaces governance and fantasy stands in for infrastructure simmers on. Its promise of freedom is seductive, but its avoidance of accountability is perilous. Ultimately, it may say more about the psychology of a handful of very rich men than it does about the future of humanity.

Wayne Gramlich still keeps up with seasteading developments and says he’s impressed with the latest designs of a Panama-based company called Ocean Designs that has workable overwater structures called SeaPods. These are people who have done their homework, he says, because they’re realized that building in equatorial waters is the best way to seastead, since hurricanes can’t cross the equator — and therefore never happened in those waters — due to the Coriolis effect. That allows you a fairly large stretch of water in the middle of the globe in which to build stable structures that can survive long-term.

“These people are definitely into it as well, the whole seasteading stuff,” Gramlich says. “But they are saying: We’re just building houseboats that float on the ocean. They’re trying to stay away from all of the silliness that comes with people trying to found their own governments.” He laughs. “I actually think they’ve done a fairly solid job.”